Um conjunto de jornalistas chamado InfoAmazonia produziu uma série de reportagens investigativas interessantes, envolvendo o uso do mercúrio na mineração de ouro na Amazônia, reunidas no site Mercúrio: uma chaga na floresta. O site apresenta reportagens sobre o uso do mercúrio na mineração de ouro na Guiana, no Suriname, na Venezuela e no Brasil. Seguem abaixo trechos especialmente relevantes para a agência social dos elementos químicos.

MERCÚRIO E MINERAÇÃO: “A mineração e comércio do ouro traçou uma marca profunda, uma linha vermelho-sangue na história da América Latina, desde que os conquistadores espanhóis submeteram as populações nativas a um reinado violento, na busca pelo El Dorado. […] Hoje, o ouro ainda é uma força econômica que move os países localizados no Escudo das Guianas, uma formação geológica de 1,7 bilhão de anos, sob as vastas florestas tropicais da Guiana, do Suriname, da Venezuela, da Colômbia e do Brasil. Mas o comércio de metais preciosos é amparado por um setor obscuro que poucos conhecem: o mercado do mercúrio, ele próprio uma indústria multimilionária. […] O elemento químico Hg, mais comumente conhecido como mercúrio ou azougue, é um dos pilares do mercado mundial de ouro. É amplamente usado na mineração de ouro de pequena escala, porque é um jeito barato e de baixa tecnologia de agludinar o ouro fino, difícil de ser capturado nos solos lamacentos. […] Quando adicionado ao sedimento, ele se liga às fagulhas de ouro para formar um amálgama. O mercúrio é posteriormente queimado, deixando apenas o ouro. Em média, os garimpeiros utilizam três gramas de mercúrio para produzir um grama de ouro, mas esses números variam muito, dependendo da técnica aplicada. Nas operações de mineração de pequena escala, praticamente todo o mercúrio usado é liberado para o meio ambiente. […] O mercúrio é uma das 10 principais substâncias químicas que representam uma grande ameaça à saúde pública, de acordo com a Organização Mundial da Saúde (OMS). Pequenas quantidades de mercúrio no corpo humano podem provocar dano cerebral, insuficiência renal e defeitos congênitos. […] A maioria dos 10 a 20 milhões de garimpeiros ao redor do mundo que trabalha em pequena ou média escala no setor de mineração de ouro usa o tóxico diariamente. Ele também polui os rios e se acumula na cadeia alimentar, impactando os ecossistemas e as populações distantes do próprio garimpo. […] A mineração de ouro representa 37% das emissões globais antropogênicas de mercúrio. […] Em 2017, foi adotado um tratado global que visa a reduzir a poluição por mercúrio, o Convênio de Minamata. Hoje 123 países fazem parte da convenção, que busca reduzir e, quando possível, banir o uso do mercúrio na mineração de ouro. […] Embora existam alternativas, até agora os tomadores de decisão falharam em fornecer aos garimpeiros da Amazônia, que dependem do mercúrio para produzir ouro de forma eficiente, ferramentas e treinamentos de que necessitem para abandonar ou reduzir o uso do metal líquido. […] Entre 70% e 80% desses garimpeiros estão presos em um ciclo de pobreza, trabalhando em operações de mineração informais e não licenciadas, onde muitas vezes são forçados a usar mercúrio pelos proprietários do projeto ou pelos comerciantes. Sem alternativas viáveis, um mercado ilícito de mercúrio floresceu, alimentado por grupos do crime organizado, por redes de traficantes e por interesses corporativos ocultos. […] Para entender o submundo do mercúrio, viajamos para as florestas da Amazônia com uma equipe internacional de jornalistas. Nós nos reunimos com especialistas, comerciantes, traficantes e garimpeiros, perseguindo o metal líquido em centros comerciais nas cidades litorâneas, ao longo das rotas de tráfico e através das fronteiras e em minas isoladas na densa floresta tropical. Descobrimos que o ouro extraído ilegalmente seguia as mesmas rotas para fora da selva e, enquanto os garimpeiros eram processados por causa do uso de mercúrio, os intermediários ficavam ricos.”

GUIANA – O metal tóxico à sombra da indústria do ouro

O MERCÚRIO ANDA JUNTO COM (SEGUE) O OURO: “Duas mercadorias que são frequentemente adquiridas ilegalmente são o ouro e o mercúrio e, na região do Escudo das Guianas, um não anda sem o outro. O ouro é o principal produto de exportação da Guiana, graças em grande parte ao mercúrio, o metal tóxico usado no processo de mineração. Em 2015, a Guiana produziu 19,1 toneladas de ouro, de acordo com registros oficiais, o que exigiu um valor estimado de 29 toneladas de mercúrio. […] Todo esse mercúrio tem sérios impactos sobre a saúde humana e o meio ambiente, mas os esforços tomados até agora para reduzir seu uso na indústria do ouro apenas empurraram as cadeias de fornecimento para a clandestinidade, deixando muitos mineradores expostos tanto às terríveis consequências à saúde, por causa da substância tóxica, quanto aos riscos legais de participar do mercado negro.”

ENTRE A FOME E O ENVENENAMENTO: “No interior da selva da Guiana, a iminente proibição do mercúrio é recebida com descontentamento pelas comunidades de mineiros artesanais e de pequena escala, que temem por seus meios de subsistência, pois sua produção de ouro depende da disponibilidade de mercúrio – também conhecido como prata-viva ou, para muitos garimpeiros, apenas como “prata”.”

PROIBIÇÃO E CLANDESTINIDADE: “Sem uma assistência maior, pouco mudará quando a proibição entrar em vigor, de acordo com os garimpeiros. O mercúrio ainda estará disponível no mercado negro – por um preço ainda maior. […] “Se for clandestino, o mercúrio fica mais caro, muito mais caro, porque é ilegal”, diz Kennard Williams, um operador de minas. Os comerciantes de mercúrio encarregados em fornecê-lo ficarão ricos, diz ele, enquanto os garimpeiros fazem “todo o trabalho duro”. […] Gabriel Lall, ex-presidente do Guyana Gold Board, agência estatal que administra o mercado de ouro, concorda que a proibição do mercúrio provavelmente “facilitará a proliferação de empresas criminosas”.”

LUCROS: “Há enormes lucros obtidos pelo comércio do mercúrio. Na Guiana, o valor no varejo do mercúrio pode chegar a 10 vezes o valor de importação. Em média, o mercúrio é importado por US$ 17,40/kg. Os atacadistas o vendem a US$ 126, mas nas regiões de mineração, o azougue chega ao balcão entre US$ 159 e US$ 234. […] Embora a proibição ainda não esteja em vigor, falar sobre mercúrio já é um tabu para os importadores licenciados.”

O MERCÚRIO CIRCULA PELA GUIANA: “Uma vez dentro da Guiana, não há restrições ao comércio ou ao movimento do mercúrio por todo o país. A facilidade com que o mercúrio avança em todas as direções da Guiana, tornou o país uma porta de entrada para canalizar aos países vizinhos, de acordo com o ex-ministro do meio ambiente da Guiana, Raphael Trotman.”

“PRATA”: “”O ouro é como pó. É tão fino que, sem a prata, você não consegue apanhá-lo”, diz ele, espalhando o líquido prateado sobre uma fina placa de amálgama.”

INDIFERENÇA: “Se o mercúrio não puder mais ser usado, Grant diz que será sua saída do setor. “Não serve para nenhum propósito sem o mercúrio, porque ele captura muito mais ouro”, diz ele. Ele está mais preocupado com o seu bem-estar econômico do que com a sua saúde. […] Não há um nível seguro de exposição ao mercúrio, de acordo com especialistas, mas Grant afirma que o mercúrio não afetou seu corpo. É uma crença compartilhada por muitos mineiros na Guiana. […] Harry Casey*, um morador de Mahdia que dirige um projeto de mineração nas proximidades, não entende por que as pessoas o alertam sobre o uso de mercúrio. “Isso ainda me deixa perplexo, por que o mercúrio é tão perigoso?”, ele pergunta em voz alta, dirigindo seu Toyota Hilux pela selva entre os garimpos. Ele sorri ao se lembrar que brincava com mercúrio quando criança, nas visitas do seu pai à mina. Seu pai usou “baldes de mercúrio” como garimpeiro e ainda está vivo hoje. “Meu pai tem 84 anos”, diz ele. “Ele fez 17 filhos com a minha mãe.” […] Equívocos sobre os riscos à saúde da mineração com mercúrio são um problema sério na Guiana. Mas os próprios garimpeiros não são o grupo mais afetado pela contaminação por mercúrio. Na forma líquida, como os mineradores o utilizam, o mercúrio representa menos risco para a saúde humana do que na forma gasosa. Os trabalhadores das lojas de ouro, que queimam o mercúrio do amálgama, estão mais expostos aos vapores tóxicos.”

O CASO PERSAUD: No meio de um dos povoados nos campos de ouro guianenses do interior, Leroy Persaud* ri nervosamente por trás da sua grande mesa em sua loja de ouro, uma estrutura de madeira de um andar, protegida por barras de metal sólidas. Em 2013, depois de quase dois anos comprando ouro das minase dos garimpeiros, queimando o mercúrio das esponjas de amálgama e derretendo ouro em pequenos lingotes, sua saúde começou a se deteriorar. […] “As coisas para mim começaram a sair do controle”, explica Persaud. Mais tarde, naquele ano, começou a acordar com dores de cabeça, a ter diarreia e vômito e foi perdendo a visão. Ele também ficou temperamental. “Acabei batendo na minha namorada”, diz ele. “Eu nunca costumava fazer isso.” Em 2013, Persaud foi à clínica local em seu povoado, onde testou negativo para malária e dengue. Seus sintomas continuaram a piorar e, após um incidente particularmente traumático, no qual Persaud começou a tremer incontrolavelmente e quase perdeu completamente a visão, seus médicos locais o enviaram para a capital. “Pensei que fosse morrer”, recorda. […] Nos Laboratórios Eureka, em Georgetown, a única instalação então equipada para testar o envenenamento por mercúrio, seus exames de sangue mostraram que seus níveis de mercúrio eram de 160 nanogramas por mililitro (ng/mL), ao menos 10 vezes acima dos níveis normais. Os médicos o aconselharam a deixar seu trabalho e a região de mineração, mas não existia tratamento disponível na Guiana. […] Uma ex-namorada exortou-o a ir a um hospital em Manaus, Brasil, mas, segundo Persaud, o tratamento era caro e ele não tinha dinheiro. Para aumentar os 2,5 milhões de GYD necessários para a viagem e o tratamento, ele voltou a trabalhar em sua loja de ouro. Quando finalmente chegou ao hospital de Santa Júlia, em Manaus, os médicos não entendiam como ele ainda estava vivo: os testes mais recentes revelaram que os níveis de mercúrio no seu sangue tinham subido para 320 ng/mL. “O médico no Brasil [me disse]: ‘Deixe o trabalho, se quiser viver'”, diz Persaud. “Mas esse é o único trabalho que sei fazer para sobreviver e [sustentar] minha família. Mas voltei preparado.” […] Persaud continua a queimar o amálgama tóxico que os garimpeiros lhe vendem. Mas agora faz isso totalmente equipado, com uma máscara e um exaustor.”

MERCURITONIMA (O TRÁFICO DE MERCÚRIO É COMO O MERCÚRIO): “As rotas de tráfico são tão fluidas quanto o próprio mercúrio. Elas mudam rapidamente, dependendo de onde a polícia concentra sua atenção e dos mecanismos de oferta e demanda em constante mudança, que ditam o mercado negro de minerais. Até recentemente, este local exato era uma rota inversa ativa do tráfico de mercúrio. Um novo posto de controle no lado surinamês do rio desviou o fluxo de mercúrio. Agora os frascos são levados rio acima, onde as margens do rio estão cobertas por uma densa floresta. […] “Ele ainda está indo para o Suriname”, diz ele, mas agora é levado para “onde não existem olhos”.”

SURINAME – A corrida do ouro ameaça o país mais verde do mundo

MERCADO e ILEGALIDADE: “A mineração de ouro é a força motriz da economia do Suriname, um pequeno país no canto nordeste da América do Sul. […] O ouro é responsável por mais de 80% da receita do Suriname em exportações. […] O país usa mais de 50 toneladas de mercúrio ao ano, e os especialistas acreditam que toda essa quantia entra hoje ilegalmente no país. […] [S]em a assistência do governo, os pequenos mineradores geralmente precisam escolher entre sustentar as redes de tráfico de mercúrio ou perder seus meios de subsistência.”

MERCÚRIO e OURO: “É o mercúrio que faz girar as economias de mineração locais. Cerca de 98% dos garimpeiros do Suriname usam mercúrio, que se liga aos pequenas fagulhas de ouro misturados à água e à lama, que são eliminadas das minas. Sem o azougue líquido, os garimpos artesanais seriam incapazes de extrair de forma eficiente o ouro preso no solo da selva […]. […] Para cada quilograma de ouro extraído, são utilizados aproximadamente três quilogramas de mercúrio, e a maior parte é liberada no frágil ecossistema da Amazônia.”

MERCÚRIO no ECOSSISTEMA: “Pesquisas mostram que quase metade dos peixes predadores pescados no Suriname apresenta níveis elevados de mercúrio. […] Mas o mercúrio não é transportado apenas pela água e pelos peixes, ele também viaja pelo ar, após sua evaporação das superfícies da água e da vegetação, ou depois que os garimpeiros queimam o mercúrio do amálgama no local. […] O mercúrio suspenso no ar pode chegar a regiões sem nenhum garimpo, como a bacia superior do rio Coppename. […] O mercúrio que já se encontra no ecossistema permanecerá por lá durante séculos.”

UM PIOR QUE O OUTRO: “O capitão maroon reclama que as minas não são a única fonte de poluição por mercúrio. As lojas de ouro em Paramaribo, ele argumenta, usam as mesmas técnicas para queimar o mercúrio e isolar o ouro. “Na cidade, eles acham que nós, residentes do interior, não somos bons, nada do que fazemos é bom”, diz ele. “Mas quando trazemos nosso ouro para a cidade, a mesma coisa acontece lá. E ninguém pode me dizer que isso não é prejudicial”.”

MERCÚRIO e MACHISMO: “A maioria dos funcionários das lojas de ouro consultada por esta reportagem não estava ciente dos danos causados pela contaminação por mercúrio ou subestimava seu impacto, o que os especialistas atribuem à “cultura machista” da indústria, à falta de acesso aos medicamentos e à natureza de ação lenta da toxina. […] Sem melhores equipamentos e educação sobre os riscos, as emissões de mercúrio em Paramaribo poderiam continuar a aumentar, enquanto os preços do ouro continuam a subir e mais do precioso metal segue seu caminho até as lojas de ouro da capital.”

TRÁFICO de MERCÚRIO: “Um motorista de táxi indiano dá um gole nervoso em uma lata de meio litro de cerveja Heineken, enquanto fica ao lado do seu táxi na Anamoestraat, a principal rua de Little Belém. Quando questionado sobre o mercúrio, ele se oferece para ir a um posto de gasolina próximo, para fazer uma ligação rápida para um traficante. Ele desliga e anuncia que um quilograma de mercúrio custará US$ 110 e que um vendedor está a caminho. […] O traficante destampa a garrafa de plástico e despeja uma pequena quantidade de prata-viva na tampa da garrafa, para provar que ele tem o produto. Quando perguntado sobre quanto mais mercúrio ele poderia conseguir, ele pergunta: “Quanto você quer?” Parece não haver escassez desse produto, e nem um único carregamento de mercúrio foi confiscado na rota da Guiana desde 2014.”

TRÁFICO: “Todos nós queremos ser sustentáveis”, diz ela [Jessica Naarendorp, diretora financeira da NANA Resources], “mas isso deve ser acessível.” […] Capy admite que precisam comprar mercúrio no mercado negro. “Não existe um local específico onde possa ser comprado, porque é proibido, assim como a cocaína, a maconha e o ecstasy. Esse tipo de coisa que você só encontra na rua porque é uma coisa proibida”.

VELEZUELA – Nas margens de Cuyuní, o mercúrio brilha mais do que o ouro

FRASE-MERCÚRIO: “Em janeiro de 2020, um veterano transportador, que sempre circula pelo sudeste do estado de Bolívar distribuindo ‘cordialidades’ em cada cidade, alcabala (como são chamados os postos de controle) e quiosque que encontra (e que a partir de agora será identificado com o nome fictício de Luis), confirma o segredo: o mercúrio circula independentemente dos decretos presidenciais ou dos acordos de Minamata, embalado em garrafas plásticas pelas estradas, ruas e rodovias nas zonas de mineração.”

MERCÚRIO e OURO: “É a única forma de capturar ouro, porque ele [o mercúrio] o une como se fosse um ímã. Se (o ouro) for de cochanos, é outra coisa, porque a pessoa o agarra com a mão”. Sintetizando: não há outra maneira de separar o ouro da terra. Somente com mercúrio isso é possível. Na Venezuela, é chamado ouro cochano o que se encontra em seu estado natural, sem ser combinado em amálgamas e sem a necessidade de processos físico-químicos.”

MERCADO (sazonalidade): “Agorinha (janeiro de 2020) ninguém tem. Deixe-me explicar: quando dezembro se aproxima, todo mundo sai disso. Então param as vendas (de mercúrio) até março, que é quando as máquinas voltam a operar totalmente. Mas é um negócio porque um litrinho disso vale um pouco de ouro”.”

MERCADO (oferta): ““It’s not illegal. This is what they use for gold”, (“Não é ilegal. É o que usam para o ouro”), explica uma vendedora de outro armazém, onde coexistem garrafas com mercúrio, chaves de fenda, isqueiros, interruptores, cervejas, refrigerantes, camisetas, bugigangas e escovas de dente. E, com o objetivo de finalizar a venda, lança uma oferta: “Um quilo, oito gramas de ouro”.”

MERCADO e ILEGALIDADE: “Por qualquer via, o mercúrio está ao alcance de quem precisar em qualquer cidade mineira do estado de Bolívar. Quatro anos depois da sua proibição oficial na Venezuela, continua sendo uma mercadoria de troca comum. Os mineiros continuam a usá-lo, poluindo os rios e se expondo a qualquer uma das consequências do seu uso. Enquanto isso, a polícia e os militares continuam lucrando com os subornos, que permitem o contrabando. Ninguém parece ter a menor intenção de se desligar desse elemento.”

ESTRUTURA SOCIAL da MINERAÇÃO: ““No mundo todo há mais de 20 milhões de mineiros. É mais lucrativo ser mineiro do que agricultor. Trata-se de legalizar e educar. Dar assistência técnica. O governo faz leis, mas não dá assistência técnica”, critica [Marcello Veiga, engenheiro metalúrgico com mestrado em geoquímica ambiental e professor de Mining and the Environment da University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canadá]. E sentencia implacavelmente que a proibição não adiantará muito. “O que serve, então? Educação dos mineiros e a presença do governo educando os mineiros. Até agora, os mais favorecidos são os contrabandistas: eles vendem mercúrio por um preço alto e compram ouro por um preço baixo. Se você fizer a proibição, isso afeta os mineiros, mas os contrabandistas, nada”.

RETICULAÇÃO: “O mercúrio da Guiana polui principalmente as águas das minas próximas a San Martín de Turumbán. Nessas embarcações que passam pelo Cuyuní (outra vítima do material) durante todo o dia e parte da noite entre a Venezuela e a Guiana está”

BRASIL – Corrida do ouro movimenta o mercado de mercúrio em Roraima

ILEGALIDADE AMBÍGUA: “Assim como a densidade, o tráfico de mercúrio é auxiliado pela ambiguidade da substância, de certa forma legal. Diferentemente da cocaína, da maconha ou do ouro, por exemplo, apesar das suas qualidades destrutivas, muitas pessoas não sabem que é ilegal, incluindo muitos policiais, disseram alguns.”

MERCÚRIO e CIGARROS: “Existem até algumas evidências que sugerem que parte do mercúrio contrabandeado a Roraima também está sendo levado para outras regiões do Brasil. No ano passado, a polícia rodoviária de Roraima, Estado vizinho do Amazonas, prendeu um homem com 150 kg de mercúrio em quatro garrafas de metal, aparentemente avaliado em R$ 90 mil, junto com 35 mil carteiras de cigarros.”

LÓGICA do TRÁFICO (mercurial): “O número de rotas potenciais mostra que o mercúrio é uma substância ágil, que pode se adaptar às diversas condições, incluindo restrições, apreensões e aumento de preço. Como muitas substâncias ilegais, acaba chegando onde existe demanda. […] “É a mesma lógica do tráfico de drogas”, disse um perito forense da Polícia Federal baseado na região do Rio Tapajós, que preferiu permanecer anônimo. “Quantidades maiores são levadas aos locais e então divididas em quantidades menores para serem vendidas”.”

RETORTAS ECOLÓGICAS: “Os grupos garimpeiros insistem que as emissões diminuíram nos últimos anos, devido ao aumento do uso de retortas – um objeto de metal que parece uma grande chaleira, facilmente disponível para compra e relativamente barata online – que pode recuperar grandes quantidades de mercúrio.”

PROPORÇÃO MERCÚRIO/OURO: “O relatório concluiu que, em média, os grupos de mineração artesanal no Brasil usariam 1g de mercúrio para produzir 1g de ouro, embora a média global seja de 3:1 de mercúrio para ouro. […] “Com um quilo de mercúrio você pode trabalhar por meses”, disse uma fonte. “Mas com tanta gente trabalhando, aos poucos os danos se acumulam.””

INTOXICAÇÃO INDÍGENA: “O uso da substância na mineração artesanal pode envenenar rios locais e cadeias alimentares. Em 2019, em audiência pública na Câmara dos Deputados brasileira, pesquisadores apresentaram um estudo que relacionava a paralisia cerebral em crianças indígenas em áreas de mineração à exposição pré-natal ao mercúrio. […] No mesmo ano, uma pesquisa da Fundação Oswaldo Cruz do Brasil descobriu que 56 por cento das mulheres e crianças indígenas testadas da reserva indígena Yanomami tinham níveis de mercúrio acima dos limites da Organização Mundial de Saúde. […] Paulo Cesar Basta, um professor de saúde pública que conduziu a pesquisa, destacou os perigos do mercúrio: sua longevidade e capacidade de permanecer durante muito tempo no meio ambiente, sua capacidade de transitar entre águas, solos e peixes e sua capacidade de se acumular cada vez mais em humanos e em outros animais.”

MERCÚRIO e ODONTOLOGIA: “Em 2018 a agência ambiental do Brasil, o Ibama, apreendeu um recorde de 430 kg de mercúrio e interceptou outros 1.700 kg, que estavam sendo importados legalmente da Turquia pela empresa química de Santa Catarina Quimidrol, que o Ibama alegou que seria desviado para o uso nas minas ilegais da Amazônia. Durante anos, a empresa importou mercúrio que era usado no mercado brasileiro de ortodontologia, cujo uso se tornou obsoleto, quando novas tecnologias odontológicas surgiram, disseram os pesquisadores.”

MERCADO: “No ano passado, de acordo com o Comex Stat do Brasil, ao menos 668 quilos de ouro, que os agentes federais acreditam terem sido retirados da Venezuela e da reserva Yanomami, foram oficialmente exportados de Roraima, apesar de o Estado não ter uma operação legalizada. […] O ouro foi a segunda maior exportação do Estado em 2019, com a Índia como o principal comprador. Naquele ano, a maior importação do Estado foram de aviões e peças associadas, essenciais para a logística do comércio ilegal de mineração de ouro.”

EBUS, Bram et al. 2020. Mercúrio: uma chaga na floresta. InfoAmazônia. Acessível em: https://mercurio.infoamazonia.org/pt/.

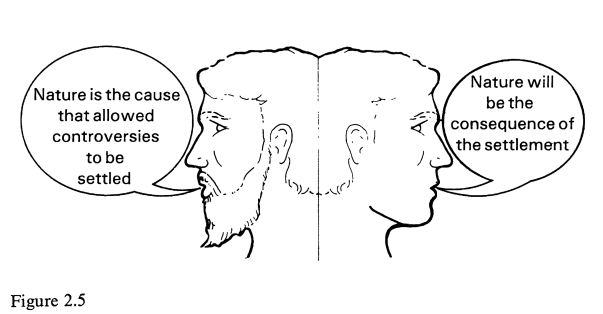

(Latour 1987:99 Fig. 2.5)

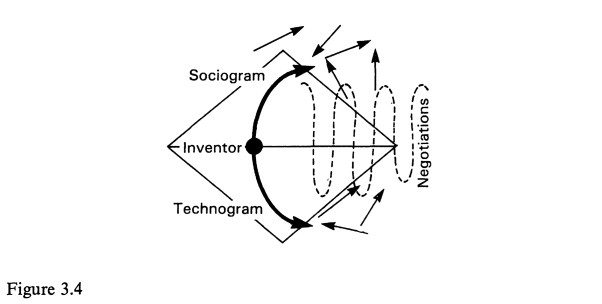

(Latour 1987:99 Fig. 2.5) (Latour 1987:139 Fig. 3.4)

(Latour 1987:139 Fig. 3.4)